Behind the Lens - stories about the making of two photographs...

Moose serendipity

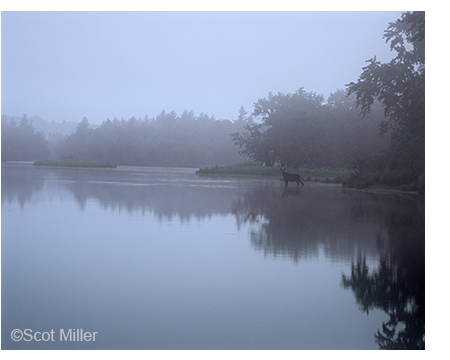

On the morning of June 22, 2012, I made my way slowly in the pre-dawn darkness from my cabin at Matagamon Wilderness on the upper East Branch of the Penobscot River several miles down a timber road and parked my vehicle at a gate where the road/trail leads to the river. After a pleasant hike (black flies and mosquitoes excepted) of about a mile and a half through the woods, I arrived at Haskell Deadwater, before 5:00 a.m. and sunrise.

What I hadn’t planned for on this day was the low-lying fog that blanketed the area, so there would be no bright first rays of the morning light from the sun as envisioned. As I studied the scene, it was dead calm. Luckily, the fog was not so thick that it obscured everything and the water was mirror-reflecting the surrounding landscape nicely. I set up my tripod and Bronica GS-1 camera with a 250mm lens, loaded the camera with film and composed this photograph. The 100-speed film, large lens and low light necessitated a fairly long shutter speed of ¼ second. I took a few nice shots of the scene and, lo and behold, a cow moose comes out of the forest and into the edge of the water in the absolute perfect place. Not only that, but after wading in several yards, she spotted me, assumed a perfect profile and stood in perfect stillness, ears erect. Click. I had my photograph! Who needed the sun, anyway? By standing perfectly still for a few seconds, she negated the normal issue of movement and the ¼ second exposure worked just fine. This photograph appears in the front of Thoreau, The Maine Woods: A Photographic Journey Through an American Wilderness, across from Jeff Cramer’s eloquent Foreword.Serendipity times two!

Less than 15 minutes after taking the moose photograph, the fog was already starting to burn off and by turning my attention and camera 90 degrees to the left, I was able to capture another lovely photograph that you‘ll find in the book on page 123. If I didn’t tell you, you would never know the two photographs were taken in the same place, so close together in time!

The Thoreau connection

In late July of 1857, Henry David Thoreau and his party traveled down the East Branch from Matagamon Lake to Bangor and would have come past this area that lies just above Haskell Rock Pitch and several miles of challenging rapids on the river.

Steam locomotives in Thoreau country!

Part of what I have tried to do with the photographs selected for the book is build a bridge from Thoreau’s day to modern day. Maine’s North Woods have not existed in a vacuum since Thoreau’s day, and I wanted the photographs to reflect that. While most are reminiscent of things Thoreau might well have seen, some—such as the steam locomotive gear and wheel, photographed near the shoreline of Eagle Lake (page 117) and shown here—allude to history in the Maine Woods since his time.

How, and why, did the locomotives get there?

There are not many places where you can be hiking through a remote wilderness and stumble upon rusting locomotives. You can in Thoreau’s Maine Woods, near the shore of Eagle Lake!

Pulpwood harvested in the upper Allagash River drainage in the 1920’s was destined for paper mills in Millinocket, on the West Branch of the Penobscot River. There was a problem, though. The Allagash flowed north, away from the east-flowing Penobscot River. To remedy this, a railroad with just 13 miles of track was constructed deep in the north woods, from Eagle Lake, running over a 1500-foot long trestle on the north end of

Chamberlain Lake and ending up at a pier on the north end of Umbazooksus Lake. During the winter of 1926-27 log haulers dragged two steam locomotives, weighing 142,000 pounds and 180,000 pounds, and sixty rail cars for carrying pulpwood in pieces overland from Quebec to Churchill Depot, then over frozen Churchill Lake and Eagle Lake. The railroad operated for over four seasons until the supply of timber was exhausted from the area. The location is so remote that the steam locomotives were never scrapped and remain, exposed to the elements, near the shore of Eagle Lake to this day.

Taking the the photograph for the book

The first time I learned about the locomotives at Eagle Lake, I was fascinated and determined to see them. It’s such an

unexpected thing to come across in the middle of the remote woods, miles from nowhere. Finally, in June 2010, I was staying at Nugent’s Camps on Chamberlain Lake, a remote place you can only reach by boat, and expressed my interest to host Rob Flewelling in seeing the locomotives. On the morning of June 25, he and his dog took me by skiff many miles to the northern end of Chamberlain Lake, dropping me off for several hours to explore on my own. After hiking about a quarter mile through the woods, I came to an opening near the shore of Eagle Lake and there they were, two rusting steam locomotives and the remains of many rail cars! In the time I was there I took several photographs with my film cameras, but the one of the weathered locomotive gear and wheel that appears in the book is the one that spoke to me the most.

The Thoreau connection

“He thought that the principal locality for the white-pine that came down the Penobscot now was at the head of the East Branch and the Allegash, about Webster Stream and Eagle and Chamberlain Lakes.”

-Henry David Thoreau, from Chesuncook chapter of The Maine WoodsEven in Thoreau’s day, Eagle Lake was a source for wood destined for mills in Bangor. On his 1857 trip, his party made their way to Eagle Lake, the farthest point north of Thoreau’s three Maine Woods trips.